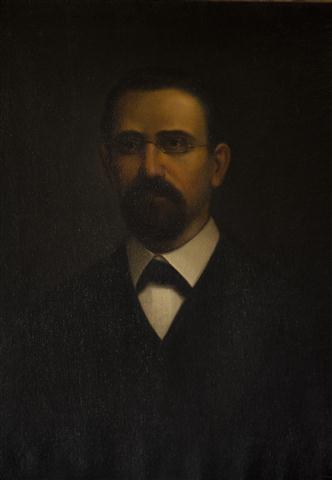

Eusebio Leal Spengler ~ Historiador de la Ciudad de La Habana ~

“Lo más precioso que todo hombre tiene: la humildad y la sabiduría”

Por: Eusebio Leal Spengler

Discurso de Eusebio Leal Spengler, con motivo de su investidura como Doctor Honoris Causa, por la Universidad española de Alicante (UA), el día 23 de septiembre de 2011

Con vuestra venia, Magnífico y Excelentísimo Rector, distinguidas personalidades, rectores, profesores, excelentísimas autoridades civiles y militares, excelentísimo embajador de la República de Cuba, distinguidas familias y amigos:

Acogiéndome a la primera palabra, la más hermosa quizás entre las hermosas palabras del idioma, a la gratitud expresada por mi entrañable y admirado amigo el profesor D. José Luis García Delgado, quisiera subrayar el honor que supone que esta ceremonia me permita unirme en sus muchos méritos y cubrir con ellos la pobreza de los míos, que esos méritos que han sido una lección de vida, que han sido fruto del trabajo intenso de un intelectual y de un hombre que sabe que toda idea ha de fundamentarse en una sólida base sobre todo cuando se trata de cuestiones del mundo, en cuestiones económicas sobre las cuales descansa el principio de la utopía, de lo contrario ella se tornaría una fantasía y no habría lugar para considerarlas o tenerlas en cuenta. Me alegro que sea en esta casa, el campus precioso y amado de Alicante, que tanto me recuerda la ciudad ideal que imaginó San Agustín, la ciudad bella donde la armonía se basa en la sabiduría, en el concurso de los talentos, en la búsqueda de la razón de ser y en el elogio de las cosas que por ser de ciencia no han de estar apartadas de la belleza y del culto natural a toda bondad humana. En la Universidad, que es la institución permanente de la cultura, aquella en la cual descansa el fundamento de la sociedad desde los tiempos en que las primeras fueron organizadas rompiendo un poco el privilegio del conocimiento que estaba solamente en el seno de la Iglesia. Pasó entonces a la sociedad civil asistido por ella, y fueron creadas las Universidades como la nuestra, una de las últimas, pero antigua si se tiene en cuenta la presencia española en el mundo del que provengo, el 5 de enero de 1728 bajo los títulos de Real y Pontificia Universidad de San Gerónimo de La Habana.

Era la vigilia de la epifanía de los Reyes Magos, y la ciudad se congratulaba con recibir en el antiguo convento de los frailes de la Orden de Predicadores, la sede de una casa de estudios, en el mismo espacio donde importantes figuras talento del dominico habían brillado, entre ellas San Luis Beltrán, Vengo de la América, de la América española, vengo también de la ciudad recordada y amada siempre por todos los que conocen la historia de la relaciones que nacieron hace tanto tiempo cuando un amanecer de octubre del año 1492, desde el balcón Atlántico de Cuba, en las costas de la actual provincia de Holguín, Cristóbal Colón, bajo las banderas de Castilla y León, avisoró un terreno que consideró tan parecido y hermoso como el de Andalucía en verano. Todo ello le recordaba la amable tierra del sur, todo ello le recordaba el sueño contenido hasta ese momento en los libros sabios de los antiguos, fundamentalmente en el libro de Marco Polo, que había visitado el Asia, o piazzetta, o los grandes viajeros europeos con los cuales había compartido el sueño, sueño que pudo cristalizar, no solamente en las noches estrelladas de la Rábida, en la Barra en Huelva, sino también particularmente, y muy especialmente, en el activo campamento de Santa Fe, donde la reina personalmente, la reina católica, le entregó los poderes propios para conquistar y abrir los mares, según el sueño que había de llevar a un marino, descendiente de Hasun, a pasar la frontera del universo conocido. De esa manera, surgió la invención de América. No llevó su nombre, no por una mezquina envidia de Américo Vespucio, que al contrario, sintió admiración por la obra colombina sino por la repetición en las cartografías de la época del nombre de aquel. Sin embargo, siglos después, cuando Simón Bolívar, padre de la emancipación que hace doscientos años sacudió a aquel continente, quiso crear su obra política y social, le llama Colombia, restituyéndole, según él, el nombre de su creador.

Hijos somos del sueño de la España transatlántica. Volvemos caballeros antiguos, llevando todavía la capa y el orgullo de aquellos fundadores que, abigarrados en sus armaduras de acero, rompieron un mundo, es verdad, para fundar otro, sobre el escombro de pirámides y dioses. Se erigió el encuentro de América y España, de las muchas Españas, tales y como las imaginó, el apasionado poeta cuando en versos que aún recuerdo y que tantas veces cito, describió los sueños de aquella diciendo: “se han vertido en ti cien pueblos, de Algeciras a Estambul, para que pintes de azul tus largas noches de invierno”.

Vengo a la tierra valenciana, que es decir algo grande para los cubanos,porque en la calle de Cordelet, en Valencia, vino al mundo D. Mariano Martí Navarro, padre del Apóstol de la independencia de Cuba, el poeta conmovido e intenso, el libertador, aquel que ejercitó la lengua española como pocos, que mereció el elogio de los clásicos de su tiempo y que permanece intacto allí, donde América y España le han colocado “cultivo una rosa blanca en junio como en enero” o aquel otro verso apasionado, que se siente en la ya citada Universidad de Zaragoza, donde compartió exilio y estudio “amo la tierra florida, musulmana o española, donde rompió su corola la poca flor de mi vida”.

Y es que estoy también en tierra musulmana o española. La primera vez que volví a ella o que vine a ella, busqué la calle Cordelet, en aquel sitio donde los tejedores de esparto habían recibido al inquieto niño de Cuba, que se convertiría, ya lo dije, en Apóstol privilegiado de su historia. Valencia me abrió sus puertas, de manos de amigos entrañables representados en el público. No los mencionaré a todos. Escogeré a dos: uno que ya no vive, allá en su tierra de Onteniente: Don Manuel Revert Nadal, que aportó a mi obra la primera historia del arte cuando éramos pobres y descalzos, nunca lo olvidaré. Y Don Alfredo Peretó Comins, que de Alzira, valenciano y fallero, me enseñó bajo el fuego de aquella tierra, donde parece que es lo más importante ver el cielo iluminado, las bellezas de esa Valencia que no conocía. Y a ella volvemos, siempre asombrado como el día que, llamado por D. Andrés Pedreño y siguiendo el signo que el profesor Louis, tan maravillosamente ha diseñado, me permitió llegar a este campus precioso que comparé al comienzo con la ciudad ideal del obispo de Hipona.

Vine a la Universidad y encontré aquí a los amigos entrañables. Primero al rector Andrés Pedreño, que hiciese el maravilloso y magnífico elogio de D. José Luis García Delgado. A él, le agradezco su bondad, cuando me recibió aquí, hace ya tantos años, particularmente a Dª Margarita Mazzella y muy especialmente a Dª Begoña San Miguel. Ellas fueron, no solamente conductoras de un proyecto, sino también transmitieron y recibieron ese amor, que es la fuerza salvadora que todo lo funda y regenera. Es por eso que, vengo como mensajero de esa tierra nuestra, empeñada desde la batalla naval del 3 de julio de 1898 en hacer su propio destino. Del alto tronco florido y robusto de la España histórica se desprendieron hace doscientos años, los sarmientos que fundaron un puñado de naciones, allá ddnde fruto de los primeros amores, nació el hijo no reconocido de Martín Hernán Cortés: Martín, tenido con la indígena que le sirvió de traductora y confesora de sueños, Dª María. Pero vengo mejor de sor Juana Inés de la Cruz, el primer estro poético del continente. Vengo del inca Garcilaso de la Vega, nacido del amor de Garcilaso y de una princesa incaica. Vengo de Santa Rosa de Lima y del primer santo americano San Martín de Porres, que con una escoba y espantando ratones, se abrió camino al cielo. Vengo de esa América, no tanto de los acorazados conquistadores de ayer, sino de los emigrantes de después. No hay una casa nuestra en que no gobierne aún desde la mesa y desde la tumba, uno de aquellos que se abrieron paso buscando un nuevo destino. Se fueron de España en la pobreza, en años de crisis, de crisis insospechada e inimaginable, de aquellos años en que se debatía la joven generación intelectual con el desastre de las colonias perdidas. Aquellos partieron, después de la fallida batalla de Annual, después del desastre de Marruecos, huían muchos del servicio militar y se metieron en los montes de Cuba.

Abrieron las tierras como leñadores de Baracoa, los fuertes leñadores de Oviedo y de las montañas de Asturias. Abrieron los caminos del mar los marinos gallegos, abrieron la tierra pinareña los canarios para plantar el tabaco y fueron nuestros padres y abuelos, llevamos su nombre, llevamos sus apellidos, nos comunicamos con su lengua que es el legado más importante de España al mundo y a América, y orgullo de ese idioma hermoso en el que se expresaron los clásicos más puros, lengua de Cervantes y de Teresa de Ávila, y si recuerdo primero a José Martí, en “su cultivo una rosa blanca…” siento detrás de mí a la santa que repite “vivo sin vivir en mí y tan alta vida espero…”

Gracias al llegar a la tierra alicantina por tantos recuerdos. Muchos amigos están en el público. José Luis ha citado nuestros encuentros frecuentes en Oviedo. Después de salir de la Magdalena, tomando ese camino gentil que pasa por Santillana, busca Cabezón de la Sal, atraviesa presuroso el puente de San Vicente de la Barquera para entrar en Unquera y contemplar la altitud de los Montes de Europa donde conquistó la fe cristiana el primer camino para abrirse paso hasta el sur de España y alimentar la esperanza.

Vengo desde Cuba que lucha, como decía, por abrir su destino. Agradezco mucho desprovisto de toda vanidad, el título que me ofrecéis. Debo deciros algo importante. Así como hemos escuchado el elogio y las palabras de respuesta de un ilustre académico, fui autodidacta. Nací en una cuna de pobreza y apenas pude concluir la educación primaria. Mi madre centenaria y venerable que está en Cuba, espera estas palabras. A ella agradezco haberme abierto el duro camino, luego la Universidad me recibió bajo condición de “suficiencia y defensa de cada una de sus asignaturas”. Fueron luchas inmensas, de noches, de semanas, de meses y de años para buscar eso que está oculto en el libro que me presentasteis en el juramento, para hallar lo más precioso que todo hombre tiene: la humildad y la sabiduría.

Muchas gracias.

Address by Eusebio Leal at the Conferment Ceremony of an Honorary Doctoral Degree from the University of Alicante

With your permission, Honorable Rector, distinguished personalities, rectors, professors, honorable civil and military authorities, honorable Ambassador of the Republic of Cuba, dear families and friends:

I would like to emphasize, embracing the word gratitude, – perhaps the most beautiful word in the language, expressed by my dear and admired friend, professor Dr. José Luis García Delgado, that it is a great honor that this ceremony allows me to join in his many merits and cover with them my humble achievements. My achievements have been a life lesson; they are the fruits of an intellectual’s tireless labor, those of a man who knows that every idea must be solidly based, especially when it comes to worldly matters, – financial questions on which the tenet of utopia rests. Otherwise, such an idea would become a fantasy and there would be no place for it to be considered.

I am pleased that it is at this university, – the beautiful and dear campus of Alicante, which reminds me of the ideal city imagined by Saint Augustine, – the beautiful city where harmony is based on wisdom, on a combination of talent, the pursuit of the raison d’être; and the praises of those things which should not be separated from beauty and the natural worship of every human kindness, even if they belong to science.

At this University, – that permanent institution of culture, on which the foundations of society have rested since the times when the earliest universities were organized and broke with the privilege of knowledge that used to be solely within the Church.

It then passed to the civil society assisted by the church, and Universities like ours were created on 5 January 1728, under the titles of Royal and Pontifical University of St. Jerome of Havana, – one of the last of the old universities, if we take into consideration the Spanish presence in the world I come from.

It was the vigil of the Epiphany and the city congratulated itself on establishing a university at the old convent of the Order of Friar Preachers, the same place where important and talented Dominican figures had once shined, including, amongst others, San Luis Beltrán.

I come from the Americas, – the Spanish Americas. I also come from the city that is always remembered and loved by those who know the history of relations emerging so long ago when in the early hours of October 1492, from the Atlantic balcony of Cuba, off the coast of today’s Holguín province, Christopher Columbus, under the flags of Castile and León, sighted land that he thought to be as similar and beautiful as that of Andalucía in the summer. All of this reminded him of that pleasant southern land, of a dream contained until that moment in the wise books of the ancients – mainly that of Marco Polo – who had visited Asia; or Piazzetta, or the great European travelers with whom he had shared his dream, a dream which crystallized not only during the starry nights at the Rabida, in Barra, Huelva, but also particularly, and very especially, in the active Santa Fe camp, where the Catholic Queen herself presented him with her powers to conquer the open seas, according to the dream leading a sailor – a descendant of Hasun – through the border of the known universe.

Thus the invention of the Americas emerged. The continent does not bear his name, not as a result of Américo Vespucio’s mean envy who, on the contrary, had great admiration for Columbus’ work, but rather because of the repetition of Américo’s name in the cartographies of that period. However, some centuries later, when Simón Bolívar, leader of the emancipation movement which shook that continent two hundred years ago, decided to draft his political and social work, called the continent Colombia, giving it back the name of its creator, as he put it.

We are the sons and daughters of transatlantic Spain’s dream. We return as ancient knights still wearing the cape and as proud as those founders who, variegated in their steel armors, destroyed a world, it is true, only to found a new one, on the ruins of pyramids and gods. Thus the encounter between the Americas and Spain began. An encounter with many Spains, as imagined by that passionate poet who described Spain’s dreams in those lines that I still remember and repeatedly quote: “…poured into you by one hundred peoples, from Algeciras to Istanbul, so you can paint in blue their long winter nights.”

I have come to Valencian land, which is of great importance for Cubans, because it was on Cordelet Street, in Valencia, that Mr. Mariano Martí Navarro, the father of Cuba’s independence apostle, was born. He was the father of a passionate and intense poet, a liberator, the one who wrote the Spanish language like few people did, who was praised by the great writers of his time and whose prominence remains intact where the Americas and Spain have placed him. “I grow a white rose, in June as in January”, as one of his verses read, or that other passionate line that one can feel in the aforementioned University of Saragossa, where he shared exile and education: “That land of flowers I love, in truth, where mingles Moor and Spaniard’s blood, for there my life emerged from bud as manhood formed from eager youth.”

And I am also in a Muslim or Spanish land. The first time I returned, or rather came to, this land I looked for Cordelet street, in that place where esparto grass weavers had welcomed that lively boy from Cuba who would become, as I said before, the privileged apostle of its history.

Valencia has opened its doors to me through dear friends represented in the audience. I shall not mention them all though. I will rather choose two: one who lives no more, there in his Ontinyent land – Mr. Manuel Revert Nadal, who contributed the first art history to my work when we were poor and barefoot, I will never forget him; – and Mr. Alfredo Peretó Comins, from Alzira, Valencia, someone who took part in the preparation of the Fallas, and who taught me the beauties of the Valencia I did not know, under the fire of that land, where apparently the most important thing is to look at the illuminated sky.

And to this land I have returned, as amazed as the day when I was called by Mr. Andrés Pedreño. Following the wonderful sign that Professor Louis designed, I was able to reach this beautiful campus that I earlier compared to the ideal city of the bishop of Hippo.

I came to the University where I found dear friends. First, I met Rector Andrés Pedreño, who sang the praises of Mr. José Luis García Delgado. I appreciate his kindness in welcoming me here so many years ago. In particular, I would also like to thank Mrs. Margarita Mazzela, and especially Mrs. Begoña San Miguel. The two of them were not only managers of a project; they also gave and received love – the saving force on which everything is founded and regenerated.

Hence, I have come as a messenger from that land of ours, which was determined to create its own destiny since the naval battle of 3 July 1898. Two hundred years ago, the vine shoots from which a handful of nations were founded, came off the tall and robust blooming trunk of historic Spain. I come from that land where Martín, the son of Martín Hernán Cortés, was born out of one of the earliest love stories with the native Indian woman who served as his translator and dream confessor – Mrs. María. But rather I come from Sister Juana Inés de la Cruz, the first poetic inspiration in our continent. I come from Inca Garcilaso de la Vega, who was born out of Garcilaso’s love for an Incaic princess. I come from Santa Rosa de Lima and the first American saint – San Martín de Porres, who opened his way to heaven, frightening mice away with a broom. I come from the Americas, not so much from those conquering battleships of years gone by, but from the emigrants arriving later.

Every home in my country is governed, either at the table or from the grave, by one of those who made their way in search of a better way of life. They left Spain in poverty, during years of crisis – unforeseen and unimaginable crisis, in those years when the young generation of intellectuals was struggling to overcome the disaster of lost colonies. Of those left, after the failed Battle of Annual, after Morocco’s disaster, many fled from military service and went into the Cuban hills. Strong woodcutters from Oviedo and Asturias mountains worked the land, like woodcutters from Baracoa. Galician sailors opened the seas; men from the Canary Islands worked the land in Pinar del Río to grow tobacco. They became our parents and grandparents. We carry their names and last names. We communicate in their language – the most important legacy from Spain to the world and the Americas. We take pride in that beautiful language in which the purest classical writers expressed themselves – the language of Cervantes and Teresa de Ávila, and if I first recalled José Martí in his “I grow a white rose…” behind me I feel the saint repeating: “I live but do not live within

and such a higher life await …” Thank you for inviting me to Alicante and for so many memories.

I see many friends in the audience. José Luis has mentioned our frequent meetings in Oviedo after I left Magdalena, taking that gentle road that goes through Santillana, leading to Cabezón de la Sal, hastily crossing San Vicente de la Barquera bridge to enter Unquera and seeing the height of the Mountains of Europe, where the first road embraced the Christian faith to make its way to the south of Spain and nurture hope.

I come from Cuba, a country struggling, like I said, to find its destiny. I very much appreciate, without any conceit, the title you have conferred on me. I must tell you something important. We have listened to the praises and response address by an illustrious academic, yet I was a self-taught person, born into poverty, and could hardly conclude my primary education. My venerable centenarian mother, who is in Cuba, expects these words. Thanks to her I was able to break through, then I was admitted to the University on condition of “aptitude and defense of each and every subject.” Those were immense struggles; nights, weeks and years looking for what is hidden in the book you have presented me with at the oath ceremony, to find the most precious things that any man can possess: humility and wisdom.

Thank you very much.

Compartir