Eusebio Leal Spengler ~ Historiador de la Ciudad de La Habana ~

Camagüey: Cuba’s Glory

3 February 2014

During the past few weeks, through to these last hours, I have witnessed, together with other colleagues and friends, the intensive preparations for this day. In fact, preparations to commemorate this date have been carried out by them for many long years. Commemorating means to remember, and every nation, family and human being needs to remember, otherwise there’s nothing left once those memories are forgotten. Hence the need to weave those precious threads of our memory, preserving the balance of different sources, which contribute to its integration and support of our identity. Thanks to such quiet and patient weaving work, culture has emerged with time. Only time and culture are capable of settling, consolidating and building what we have gladly seen and enjoyed.

Last night, in particular, we enjoyed moments of special and great emotion when elderly locals – including those who no longer live here but have never forgotten their hometown – were called to the front row. They were joined by current residents, some of whom are very young, to enjoy this marvelous and beautiful show, or rather cultural event. It is usually called an activity, but the word activity detracts from the event’s significance and foundation. An event is always an act of creation. And last night we were witnesses to an act of creation that could not have been possible without many elements that should be noted today.

Firstly, there is the past, historical, and therefore, inexorable event. As I have said on previous occasions: “History is not as we would like it to be, but as it was.” It did not begin in this part of the world only after 1492, even though the discovery of the Americas was an extraordinary and exceptional event, bringing about the collapse of medieval and pre-Renaissance concepts on geography and the Earth’s place in the universe. Those concepts were cause for a long-standing discussion since Copernicus’ and Galileo’s days. The Earth as the center of the universe had become a blue spot in the infinity. As Mr. José Mujica – that important Uruguayan leader – said a few days ago: “As from that moment, we were nothing but a small mineral fragment in an infinite universe.”

Such an event, however, changed our concept of the world – as nearly all ancient philosophers and thinkers had imagined. Although the illustrious Séneca, of Spanish birth, had virtually prophesied: “Certain times will come, when ties keeping things together will be brought to the surface of the oceans and sea, and a great land will open up. A new sailor, like he who was Jason’s guide, (…) will discover a new world, and the island of Thule will no longer be the farthest land.” Those “certain times” came after music, architecture, mathematics, and all forms of modern thinking expanded. New geographical concepts were then established, and they contributed to laying the foundations for that great discovery, although, as we were told at school, “finding the shortest way to India was the purpose for that trip.”

But where had they really arrived? If, for a moment, we put ourselves in those sailors’ place, where were they in reality? Just a few years later, the existence of the New World was proven. That world was a vast continent with lush vegetation and large rivers like the Orinoco, whose turbulent waters impressed Columbus so much that he thought it was one of the great biblical torrents. He had believed, with no level of certainty, that this – apparently infinite – archipelago, was Cipango (today’s Japan). Therefore, he expected to find the Great Khan or some Cathay prince, in the middle of today’s Holguín province. The Great Admiral, imbued with the beauty of our landscape, uttered words of admiration, which could be repeated even today with justified passion, as we contemplate the eastern side of Cuba:

“This is the fairest isle that ever eyes beheld.”

Following the same train of thought, and flicking through the pages of history, I could remember those verses that we also learned at school. They marked the deep pain of someone who would forever become one of the greatest Spanish-speaking poets of all generations. As she stared at the horizon, having been robbed of her homeland at a very young age for reasons beyond her control, Gertrudis Gómez de Avellaneda exclaimed:

“Pearl of the Sea! Western Star!

Beautiful Cuba! Your bright skies

Are covered by the night’s opaque veil,

As my sad forehead is covered by pain.

I am departing! ….

Diligent plebs are hoisting sails

To deprive me of my homeland,

And a warm breeze is soon coming from within (…)”

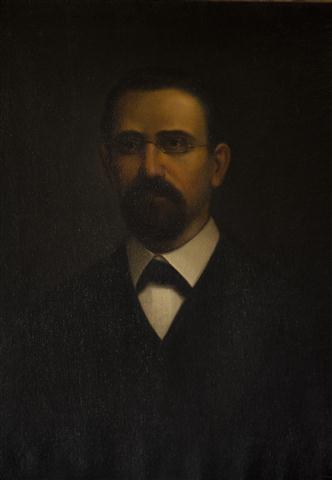

Last night we were watching her famous portraits – that of her young and austere face, dressed in a gold-like attire, painted in oils by Seville-born Antonio María Esquivel – a piece that is displayed at the National Fine Arts Museum; also that other image, in her later years, when she was crowned with laurels, during a ceremony that Cuban intellectuals organized in her honor at Havana’s Opera House.

This year – the 500th anniversary of the founding of Camagüey – is also Tula’s [Gertrudis Gómez de Avellaneda’s] 200th birthday. The daughter of Puerto Príncipe had unwittingly followed in the notable footsteps of José María Heredia who was born in Santiago de Cuba. And both are immortal, as they enjoy the privilege exclusively granted to poets, singers and minstrels – the invocation of their memory with each repetition of their verses.

During the course of these days, I have willingly and passionately studied the history of what has been called transhumance in this town, which was originally established somewhere in the north coast, by the bank of today’s Nuevitas Bay – sighted by Columbus during his first voyage. That first settlement would have been founded as Santa María del Puerto del Príncipe town on 2 February 1514 during festivities dedicated to Candelaria – owner of the sea and wind, and patron saint of the Canary Islands. However, its coastal location would be abandoned in search of other areas inhabited by aboriginal population, near the newly-found gold-panning sites, including Caonao chieftainship – sadly famed for it having been the place where a killing of native Indians had been perpetrated by Pánfilo de Narváez and his army in 1513.

We know of these events from Father Bartolomé de las Casas who had relinquished his right to control land and Indians, following the example of Dominicans in Hispaniola. They had become preachers of a new type of humanism, decisively opposing such methods of exploitation on the basis of a greater sentiment – that of American men seen as human beings, and not beasts able to reproduce sounds as any other wild animal creature. It was thanks to Brother Bartolomé’s attitude that the Pontificate eventually acknowledged locals – that is, American Indians – and their human nature at the historical debate known as Valladolid Meeting. Colonists’ greed, however, did not abate. So, it is known that an Indian uprising led, in 1528, to the moving of Puerto Príncipe to what would be its final seat – a place equidistant from both coasts, between Tínima and Jatibonico Rivers.

It is important to note that towns founded in Cuba often had an original settlement that would be moved to a different site, which became their final location. The same happened with San Salvador de Bayamo and Santísima Trinidad, which are both celebrating this year their 500th anniversary. The latter was originally founded by Governor Diego Velázquez on the banks of the Arimao River, near Jagua Bay, and it was not until mid-1515 that it was moved to its current location at the foot of the majestic Escambray Mountain Range.

As for Bayamo, suffice to say that its relationship with Camagüey grew through Silvestre de Balboa, a poet from the Canary Islands who was based in this city where he worked as a Town Council clerk. It was here that he wrote his Espejo de paciencia [Mirror of Patience], a literary work dated 1608, which testifies to the beginning of Cuban literature. His manuscript is among the papers kept by Bishop Pedro Agustín Morell de Santa Cruz. That poem relates to the early black hero Salvador Golomón’s epic battle, when he cut off pirate Gilberto Girón’s head, saving the Island’s bishop Mr. Juan de las Cabezas y Altamirano, who was visiting that native Indian land in Bayamo – land of the Saviour.

Yesterday, when our plane’s wings smoothly descended on Camagüey’s land, we enjoyed an aerial view of what is known by locals as the savanna – so-called by Bartolomé de las Casas: “… a large grassland of more than ten leagues.” He described it as “very good land”, which indeed it has been over the years, with thousands of cattle pastures emerging from its fertile soil which also produced red clay for old Roman- and Arab-style roofs, walls and large earthenware jars. Today, they adorn the courtyards of the oldest houses which proudly bear “The Camagüey,” potters’ identity seal. It would seem as though this city’s history, which is Humankind’s history as well, was imprinted in the clay of those indestructible jars.

You have to know the symbols to be able to go deeper into that history. It’s the history of the passage of those lords whom – like the Four Horsemen of the Apocalypse – entered this land, each one bringing invention and modernity with great violence – horses, gunpowder, steel and the wheel. And in the face of such an imperative, the most powerful of empires fell upon the Americas – those of the upper Mexican plateau and thousand-year-old Peru – while Mayans in Central America were being driven to extinction a long time before. As for our indigenous people; “neither mine nor yours” as the great chronicler Pedro Mártir de Anglería put it – they succumbed to the sword, disease and grief. They became a mere drop of blood lost in our veins. Their names have survived, however, in our cities’ last names – Nuestra Señora de la Asunción de Baracoa, San Salvador del Bayamo, Santa María del Puerto del Príncipe del Camagüey, San Cristóbal de La Habana, and only cities like Santísima Trinidad, el Espíritu Santo (Sancti Spiritus), San Juan de los Remedios and Santiago de Cuba – the second Santiago in the Americas – have remained to testify to the conquistadors’ ideology.

Election principles were established in our continent on the basis of the Town Council – an institution from Castile. No wonder it was praised by José Martí, when he said: “The municipality is the root and the spice of freedom.” That institution represented the rights of those chosen ones, whose names appeared later in history as lords of a patriarchal caste, but who did not hesitate at a specific moment to give up their privileges in search of greater things. Contrary to other parts of the world where members of that caste clung on to their class power, what then happened here was that they relinquished that power in the name of an ideal involving victory of the development of ideas over the status quo.

That is why, when I attended the ceremony at the Square this morning, I noticed the four palm trees as a reminiscence of Joaquín Agüero’s and his fellow countrymen’s sacrifice in 1851. On the occasion of a primal anniversary of that event, I wrote an article at the request of former Rebel Army Captain Jorge Enrique Mendoza Reboredo – a radio announcer of lovely diction from Camagüey – to vindicate that patriot. The idea is that, in those days, Agüero could not be absolutely, clearly and definitively convinced that full independence was the solution, because such sentiment would only appear later. That is what we saw at the museum that has fortunately reopened, thanks to the selfless work by our nation’s cultural heritage workers. The Lugareño’s (The Local’s) ideals, which were so influential at that time, would have evolved until he understood that such freedom was possible without the need to turn to our powerful friend from the North, whose plans apparently had to be accepted by Cuba by some sort of natural or geographical mandate.

Of those precursors, Agüero represented the birth of a legend that is united – however tragic it may seem – to the memory of the one who was called Bayardo by many generations. The latter kept a handkerchief with that patriot’s blood, perhaps as an early warning of his liberational vocation. That beautiful house that today we see across from La Merced convent was turned into headquarters for the Spanish troops that occupied the city after the patriotic uprising of 4 November 1868. It was in that house under a noble coat of arms, where that handsome young man’s parents and brothers lived while he walked the streets of Havana when he studied at Saint Gerome University or Saint Charles and Saint Ambrose Royal University College. He had long hair, wore a diamond ring, and was fashionably dressed, making the most of his composure and pride. He was a privileged young man who was called to a destiny that was not his own. That is why, our great poet Silvio Rodríguez rightly said in a song, which became an anthem on this land when Fidel spoke at this square commemorating that fateful day of 11 May 1873: “Mortales ingredients / armaron al Mayor, / luz de terratenientes / y de revolución …” [“the Major – a Beacon for Landowners and for the Revolution – / Armed himself with Mortal Weapons (…)”]

Ignacio Agramonte was baptized at La Soledad Church, the same place where he married one of the loveliest young ladies in Camagüey – Amalia Margarita Simoni Argilagos. Last night, one of the most beautiful moments of the ceremony was when some of the love letters they wrote to each other were read. Those were romantic moments – and let us stress the actual meaning of that word – because those patriots were as romantic as they were liberal, freethinkers and in favor of emancipation. It would then seem odd for a Cuban that that young man had once avoided a flirtatious kiss on his cheek, because he thought that it only belonged to his beloved Amalia. Due to his harsh nature, Agramonte was described as “a diamond with the soul of a kiss” by José Martí – Cuba’s Apostle.

That kiss extends to the other sons of this land – the Varonas, the Zayas, the Bazáns, the Montejos, the Loynaz, the Arteagas, the Betancourts, the Molas, the Lorets de Mola, the Arangos, etc. A great part of those illustrious men who represented Camagüey’s noble power, joined the uprising taking place on 4 November in Las Clavellinas. Incidentally, Ignacio was not there. He was in a distant place at Oriente sugar mill in Sibanicú, near the site where he had spent his delightful honeymoon at the powerful La Matilde farm owned by his father-in-law Doctor José Ramón Simoni. According to General Enrique Loynaz’ testimony, which was corroborated by his daughter Dulce María – the eminent poet – who told me, the newlyweds’ initials were still preserved on a tree when he arrived there in 1895 as part of Antonio Maceo’s invading column.

In those days, La Matilde farm was already in ruins, and vulgar insults against the independence cause written by Spanish soldiers billeted there could be read everywhere. However, there was something different on a white and blue window – a poem of unquestionable literary value, illustrated with a pyramid crowned by the Spanish flag. General Loynaz said that in response to that symbolic gesture, he painted the Cuban flag and wrote verses below its mantle that would become the Invading Anthem by Maceo’s express decision.

Now, I beg forgiveness from those who think that history can be summarized in political and administrative terms. These five centuries of our history need to be celebrated at every home in Camagüey, from across Jatibonico [River] to Jobabo River’s currently poor waters; that is, the Great Camagüey. People in Ciego de Ávila must be feeling it as their own [celebration], because it was on its pine fields that Panchito was born. He was the son of a jiguanicera [a woman from Jiguaní] and a rebel leader from the Dominican Republic who made his way in this land after El Mayor [The Major] had passed away. When Carlos Manuel de Céspedes – described by Martí as a man of great passion, strong and flawed like a volcano, – asked for Panchito’s services while the latter was temporarily suspended, Gómez modestly, though arrogantly, replied: “Mr. President, here is your old soldier.”

And what was the task? To come to Camagüey, where Cuban constitutionality was conceived at that summit meeting held in Guáimaro on 10 April 1869. It was also there that the voice of the one who would be, without doubt, the Sucre in this story, was heard. Because of his talent, his knowledge of law, his vast understanding of culture, and his European experience – in spite of his being part of a different generation – Ignacio Agramonte should have been the rational successor to the Father of the Cuban Nation. And among all the women in attendance, Ana Betancourt clearly excelled. It is only right that the highest award of the Cuban Women’s Federation is named after her, as was late and dear comrade Vilma [Espín]’s express wish. It was Agramonte who read the letter in which she asked Cuban legislators that, as soon as the Republic was established, women should be granted the rights they were deserving of in all fairness. There, at Guáimaro, the relatives of the other Ana from Camagüey – Ana de Quesada – were present. She was the young lady who married Céspedes out of love, in spite of their marked age difference. She would bear him twins that he did not have the privilege to meet, as they were born in exile – Gloria de los Dolores and Carlos Manuel. What a symbolic name for the daughter of that woman from Camagüey and that man from Bayamo! Gloria de los Dolores! [Glory of Sorrow!]

The Father of the Cuban Nation succumbed on 27 February 1874 in San Lorenzo, on the top of Sierra Maestra Mountain, where he lived in isolation after he had been removed from office as President of the Republic in Arms. Three years before, leaving discrepancies aside, he had offered Agramonte military leadership of Camagüey. The latter reassumed leadership when the rebels’ situation became difficult with the Spanish troops’ charge. From that moment on, Cuban patriots went on the offensive thanks to the momentum of the Major’s famous cavalry. Following a surprise attack on Colón Optical Tower, they victoriously fought a series of combats until they reached glory in the heroic rescue of Brigadier Julio Sanguily; this episode is regarded as one of the most extraordinary military actions in our history. Later came Cocal del Olimpo and other no less glorious battles, where Las Villas rebel troops were also under the Major’s command.

Then the tragic events of 11 May 1873 occurred, when he [Major General Ignacio Agramonte] was killed on the battlefield at Jimaguayú, about 30 kilometers from here. Agramonte preceded Céspedes in laying down his life for freedom of his country. His body was brought to this square, which should have the same halo of sadness as San Pedro Alejandrino in Santa Marta, Colombia, where Bolívar expired. The Major’s body was taken on a cot to San Juan de Dios Hospital where Father Olallo – a saint for Cubans – washed his mortal remains and prayed before the corpse, in defiance of Spanish soldiers. The body was cremated in total silence, using firewood and oil, whilst the houses of the families of those who had taken up arms remained closed. Terrible challenges hovered over Cubans in that long and bloody war.

Let us go back to Máximo Gómez. He arrived in Camagüey, and what did he find? The Major – the President’s natural successor – was dead. As a man who respected the Constitution, Agramonte would have never allowed the leader of the Revolution to have been overthrown on that terrible day: it was legal, but not moral; legal, but not ethical; legal, but blind – as justice is usually portrayed. He would have been, without doubt, the successor of the Father of the Cuban nation.

Now, in their place, came Gómez the intrepid, the victor in Ventas de Casanova – the first machete charge in Cuba’s independence wars. Here, Camagüey’s troops awaited him with some distress. “Who’s coming?,” he was asked at the border. “The Major was only one, and he died in Jimaguayú,” a few claimed. But now the Dominican was the chief of the invading contingent who had to be obeyed. And as chief, he knew what awaited him. The heroic cavalry from Camagüey was under his command, with men of considerable stature such as brigadier Henry Reeve, among other bold fighters. To prove himself, Gómez wrote on this land four of the most glorious chapters in Cuba’s war – La Sacra, Palo Seco, El Naranjo and Las Guásimas de Machado. In addition, there was his surprise attack on Ciego de Ávila village after a rainy night.

No one who has been born on this land can give up such glory. That is why I said: “Celebrate that day everywhere, in Morón, in Júcaro, on the other corner of the military path that was chosen to block his way to Las Villas.” That is where Gómez was wounded on 6 January 1875, when he ordered the battle cry to the west.

Twenty years later, the meeting which finally led to the formation of the Invading Army, was held on Lázaro López’ land. At a solemn ceremony, Gómez and Maceo were recognized as leaders by representatives of the government of the Republic of Cuba in Arms. It was then that the latter received the Cuban flag, embroidered by Camagüey’s daughters, to head the troops’ march to the west. He exclaimed, by way of an oath: “I shall carry this flag to the west, or will return wrapped up in its pleats!” The Bronze Titan’s letter expressing his gratitude for being the repository of the newly-formed Republic’s flag “exquisitely done by Tínima’s virtuous daughters” has also survived.

Oh, our nation’s glory; oh, Cuba’s glory! It could not be contained in one single speech. It would be absolutely unthinkable to refer to its history by only talking about its architecture or its beauty. There is something that Miguel [Barnet] pointed out today in his beautiful lecture – the value of the intangible. First comes the feeling, then the knowledge. Each family teaches its children, before they go to school, to love their homeland, their neighborhood, their nation, their flag … that flag which was washed in so much blood and sacrifice, and was chosen in Guáimaro, with no offence to that other flag carried by Céspedes when he crossed Jobabo river; that had been made with the veil covering his dead wife’s portrait.

Today is a big day – a festive and joyful day. It’s been five hundred years since this town was founded! We are the fruits of a thousand peoples coming together on this land to form what could be termed a small human race, in whose veins Spanish, African, Muslim and Oriental blood flows.

It would be inexcusable not to thank our institutions, our Party, the local government and its people for their hospitality; also, the City Historian and his Office for having led a movement that has inherited the noblest will of the people of Camagüey, at great sacrifice, asking for nothing else in return.

It is essential to preserve our heritage, because it is our parents’ names resonating in the stones, walls and bells. Everything can be explained, even painful discrepancies and confrontations, with no omission or silence, without removing a single page from our history because of sectarianism or discrimination.

National unity was only consolidated by the man who spoke at this square one hundred years after Agramonte’s fall. Today it [national unity] is supported by the one who carried the flag on that historic 28 January Torch March. That Cuba has been unbeatable until now, because we have resisted and persevered. That is why the Heads of State of Latin American nations are now rectifying positions of yesteryear, when the empire imposed isolation on us. They need to know that we are prepared to defend our nation’s everlasting honor … with poetry, with words.

Glory to Camagüey!

Compartir