Eusebio Leal Spengler ~ Historiador de la Ciudad de La Habana ~

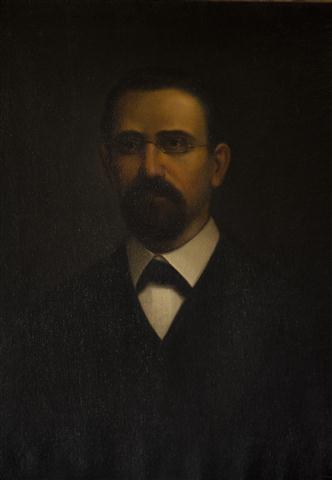

Emilio Roig – the Eternal Havana City Historian

Extract from an interview granted by Eusebio Leal Spengler to Television Director Santiago Prado.

When Emilio Roig was born at 40 Acosta Street, in August 1889, no one could have anticipated that the times he lived in would be so complex and important for such an intellectual.

He was born in 1889 and US occupation began almost one decade afterwards. That period of his life was a prolific one, because it was the time of Cuban insurgency, of the great emancipation war, and what years later he would define as José Martí’s revolution or war.

His upbringing at the family home and the human environment around him greatly enriched his childhood, as well as the lives of his parents and sister, whom he dearly loved. Emilito has, as we all know, German blood from his mother and maternal grandfather German de Leuchsenring, who was Honorary Consul-General to Havana, and owner of an important pharmacy on Obispo Street; and of Catalan descent from his father’s side, who gave him his first last name Roig.

But Roig means red, and that young boy, without any political affiliation – not even to the Communist Party – would be called “red” a few years later. He was very close to and enjoyed Julio Antonio Mella’s and Rubén Martínez Villena’s friendship – and these are the first names to be mentioned. Later there were others who were also his dear friends and almost contemporaries, such as poet Juan Marinello, who was introduced by him in the Social journal pages as one of the most original Cuban intellectual figures. Mella did not hesitate to write a dedication to him that read: “To Emilito, an expert in these matters against Yankee imperialism.”

This means that in the early years of the Republic, based on the bitter experience of an intervention in Cuba, not once but twice, he developed the sentiments of the deepening undercurrents that, from Father Varela onward, reinforced the dream, the expectation, the hope and utopia of a true Republic: “with all, and for the good of all”, as dreamed of by Martí, – a truly sovereign Republic.

The conditions under which Republican Cuba was born and Emilio Roig lived through his youth and adolescence, were years of disorientation, when characters moved in one direction or another, sometimes creating shadows and silhouettes that were difficult to notice and place in a cultural or psychological context. I remember his conversations with General Enrique Collazo and the latter’s loving dedication to Emilito in Mr. Collazo’s book Heroic Cuba. In the brief foreword General Collazo speaks of oversight of our martyrs’ mothers, of our Republic being an orphan, of betrayal of the foundational ideals for which he and many others had fought.

That is why it is not strange that Emilito, with that temperament arising in him and his love of the graphic world rather than the toga, would move from law to journalism, to Carteles and Fígaro magazines, where some of his works would be published. Later, he also took part in the most important gatherings held in Cuban intellectual circles. He used to tell me, for instance, about a gathering at El Naranjal, a shop on Obispo Street, one of those stylish cafés in Havana, with its marble top and Viennese chairs, where various groups usually gathered around outstanding figures, such as Mr. Manuel Sanguily, from whom he heard so many important testimonies. Sanguily was not only an eloquent man with a very Cuban manner of speaking, but he also had neat and beautiful handwriting and was, in addition, an unbeatable collector of testimonies to the great struggle from diaries, documents and letters about the Independence exploit, voluntarily given by liberators, at his request.

They also met at José Antolín del Cueto’s office, one of the most important lawyers in Havana back then. [José Luciano] Franco passionately told me about that, and not only about José Antolín’s personality, which today is almost forgotten, but also of the young people gathering in that place who would later show up at other not less important lawyer’s offices, such as that of Mr. Fernando Ortiz.

It was precisely in that office where Mr. Ortiz would have two of the people who most greatly influenced Emilio Roig’s childhood as his assistants: poet Rubén Martínez Villena and journalist Pablo de la Torriente Brau. Both were radical revolutionaries and intensely Cuban. One was born in Alquízar; the other in Puerto Rico, but his passion for Cuba and his commitment to the ideals of revolutionary Cuba were unquestionable. In fact, the smiling Pablo was one of the most likable, wittiest and sharpest of critics of Cuban reality. In Emilio Roig’s collection of letters, which is now being published, there are letters from Pablo that María Benítez showed me on many occasions, as well as the amusing notes he wrote when he was imprisoned on the Isle of Pines. He told Emilito, for instance, about young poet Juan Marinello’s arrival in jail. Marinello was used to urban refinement and, according to Pablo, he was beginning to proletarianize in prison, somehow referring to his natural inclination to quickly recognize the working class as a fundamental revolutionary strength in the Cuban society, as Mella and Martí had done earlier.

Emilito was brought up at that time. He arduously lived through the creation of the Minorista Group, of which he was its soul, and so he was portrayed by his friend Conrado Massaguer in a caricature immortalizing the group, where the main figures are depicted, including Mr. Fernando Ortiz. There was Emilito together with the members of that group, eloquently explaining and speaking to them, as was his passion. Rather than a writer, he was a great lecturer and his writing was characterized by shrewdness and dynamism in his articles highlighting the character of the journalist he was until the end of his days. The most interesting thing about his biography is to be able to follow his trace through the Cuban press. Until his death in 1964, he kept commitment to writing a chronicle for Carteles magazine. The factitious collection of archives contain all of these articles, which he turned into a guide for those articles he would write later, or as notes for his most important books.

He was a devout follower of Martí. He convinced himself that it was not possible or decent to think of Cuba if its historical anti-imperialistic nature was not recognized. He was respectful of other people, but irascible in the face of treachery, and volcanic, as Raúl Roa would describe him. In his panegyrics and debates he confronted certain news media giants of the time, such as Diario de la marina, after that period when some of the most important figures representing the ground-breaking, educated, upright and revolutionary thinking of the Cuban society were momentarily allowed to write for the Journal, and then it was as it had always been – the voice of all Anti-Cuban trends. Emilito’s struggle against it, especially during those turbulent and sad days when the Journal fought tooth and nail to defend the Spanish Republic, was memorable.

No fair cause, no human cause and no rights violations were ever alien to him: he fought for the Palestinian people, for the fair cause of Puerto Rican political prisoners – a commitment he made at an early stage when he met Mr. Pedro Albizu Campos in Havana towards the end of the 1920’s. Mr. Albizu arrived in Cuba bringing a personal letter to Emilito from Marti’s friend – Federico Enrique Carvajal, describing Mr. Albizu as the person to continue Ramón Emeterio Betances’, Duarte’s and Martí’s ideas and struggles. Only in this great context can we understand the man who accepts the importance of being the Havana City Historian, because Havana is the capital of Cuba, but Havana also brought together a number of elements of its history, its tradition and institutional system that have required and will always require a special approach.

Havana had its University, which was the only one back then; Havana had its St. Charles and St. Ambrose Seminary which, together with that of St. Basil the Great in Santiago de Cuba, had also experienced a relatively short period when some of the prominent figures of Cuban thinking coincided.

Havana, a city of Architecture and History, was founded in 1519. It was to Havana that the City Historian dedicated some of the best time of his life, especially when he decided to preserve the Town Council Minutes and met his dear friend Genaro Artiles, a Spanish Republican paleographer, who arrived in Havana and was asked by Emilito to set up a small paleography school. The idea was to give the 16th-century Town Council Minutes to the printing office, after those early years had been transcribed, deciphered and decoded. Deciphering the handwriting in those Minutes required a paleographer’s work, because not only was the ancient notaries’ procedural style still a significant feature, but also many of the Arabic forms of handwriting were still preserved at that time. The publication of the first volumes of Habana, apuntes históricos (Havana, Historical Notes) coincided with the appearance of the first volumes of the Havana Town Council Minutes, which were the Historian’s major endeavor.

Four things were promoted by him from his position – the City Museum that was set up back in 1941-1942, the period when the funds for the Museum were searched for and collected; the Lecture system that was the living word; a Library, named after Francisco González del Valle, that was turned by him into a circulating library and, with his friends’ support, came to be one of the most important libraries of the time in Cuba; and something very important – an Archive , where Martí’s letters to Mercado, letters by Bolívar, photos of the great Cuban national heroes, would be eventually found, a true wonder from which he always took what was needed for his huge endeavor that today would have to be published as a complete work.

On the Monument Commission:

Emilio Roig was a founder and creator of Institutions. He founded the Cuban Society for [Historical and] International Studies. He played a leading role in the anti-imperialist league, where he regarded himself as heir to and continuator of Julio Antonio Mella’s work. In addition, he strongly promoted the idea of a national board for the study of Afro-Cuban folklore and traditions, for which he combined efforts with Mr. Fernando Ortiz, who was, without doubt, the master in this field. He was also the creator of the first National Commission for Historic Sites and Monuments. He managed to have the monument declaration drafted in favor of important places in Cuba, such as the city of Trinidad, where he had the support of his great friend Bécquer. He gave his support to the creation of the Santiago de Cuba university – the Universidad de Oriente, where another great friend, Felipe Martínez Arango, struggled.

He was also an avid collector, a fighter for preserving the tangible heritage – the monuments that were being lost. For instance, he joined Fermín Valdés Dominguez and other young people to preserve the wall where the students had been executed in 1871; he stood up for Paula Church – now a National Monument and the venue for ancient music band Ars Longa -, against the destruction intended on that ruin by the urban tramway expansion works.

He defended Havana Cathedral as a whole and dedicated a beautiful book to it as a National Monument. He succeeded in supplanting the statue of the abominable monarch Ferdinand VII, whom he regarded as a museum piece, with the monument to Carlos Manuel de Céspedes at Plaza de Armas (Parade Ground). In this regard, it is appropriate to mention that Ferdinand VII was in power and Roig saw the whole Republican corruption, the political class’s genuflection and the public shame involved in the last pre-revolutionary period, embodied in the figure of the felon king, which he intended to replace with that of someone who, paradoxically, had no monument in the city of Havana, except for one that had been erected by two teachers – Hortensia Pichardo and her husband Fernando Portuondo – at the Institute in Víbora municipality.

It was then that he commissioned the statue of Céspedes that was placed at Plaza de Armas and entrusted José Manuel Cortina, one of the greatest Cuban orators of all times, with the praises of Céspedes.

Consequently, Roig was also controversial. He brought a lot of problems on himself. And I don’t mean to say that he was a perfect man – as I would not like future generations to say that about me or any other living person, and especially about any political or cultural figure.

Roig had his passions; he caused a lot of hassle, sometimes for good reason under specific circumstances or at certain moments, but none of this can cloud or tarnish the outstanding role he played in the Cuban historiography and in the promotion of a school of thought where the free thinker that he was prevailed.

He was a staunch layperson. He believed in laicism as an achievement of revolutionary, insurgent and Republican Cuba. He believed in a free school – a dogma-free school with no religious affiliation of any kind. He was not a member of any political party; he was regarded as a friend by communists and was always held in respect by progressive men of all parties – he was incorruptible.

Born to a bourgeois family, he died in a very simple house on Tejadillo Street with no other possession than his small library and personal belongings, all of which I was able to count and fit in this room. What could not fit in this room is his work – a work that has prevailed, a work of speech, of passion, of loyalty to Cuba, a work where he believed and categorically claimed that without the knowledge of that history, the Cuban people and the Cuban school would never be able to find their true course.

In his monumental work Historia de la Enmienda Platt (History of the Platt Amendment) he stated the character of our struggle against the US Empire – bitter enemy of the Cuban pro-independence project from its roots. He traveled all over our continent with his friends placing monuments to Martí and Maceo. He supported Ruy de Lugo Viña’s effort to create an International Organization of Capital Cities, which was set up in Havana. He was a great friend of the Cuban Freemasonry – even though he was a layman, he was awarded the Freemasonry gold medal, because he recognized their role in the History of Cuba and identified their symbols in our flag and coat of arms.

Emilio Roig’s Legacy:

Without his legacy it is impossible, at least for me, to do anything. Roig is and will always be the eternal and paradigmatic Historian of the City of Havana. There is or will be no other with his qualities. No one can match him, because the times he lived in shaped a man of two centuries – an exceptional man, a knight of the spoken word who was fearsome in polemics and a friend of all fair causes. He was always seen with suspicion by those who listened to him at a platform or read his writings – and that is his legacy. A legacy that, to a great extent, has been developed thanks to the means available today – he could use the radio, but mostly used the newspaper, the press, and periodicals. He held on to that and was editor in chief for Social magazine. Massaguer was his close friend and also an artist who gave Roig a society page magazine that he turned into a Cuban culture magazine, as important as Orígenes, just to mention another example.

His times were not those of the television; these are our times – we have learned from his hand and I made the most of the time I spent in his company. I am forever in his debt. Without Emilio Roig and, what’s more, without María Benítez, there would be no Eusebio Leal. María was widowed when she was still young and was loyal to that legacy until the last moment of her life. She kept his papers, his documents, his work, which she could see consolidated, and fought to the death to defend it, because I not only inherited his work but also some of his enmities who are by no means worthy of note, as Roig’s work is here and lives on. We’ve done our bit to erect the pedestal for his monument.

Compartir