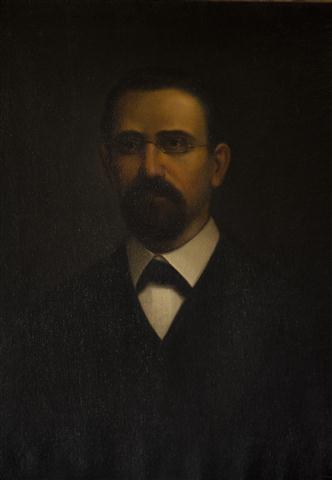

Eusebio Leal Spengler ~ Historiador de la Ciudad de La Habana ~

Interview with Eusebio Leal: Restoration of Old Havana – a Mirror of Cuba

Por: Oliverio Comte / Taken from Cubadebate

29 July 2008

Every living thing struggles to survive and so does any social process. In a world ravaged by the storm of globalization, where modern emperors wish to impose a neoliberal dictatorship at any cost, the defense of people’s cultural identity is a duty that cannot be waived. The power centers, led by the United States, promote a “cultural shock” aimed at imposing an unequal order to protect the privileges of a minority alienated with profit. The crisis of the system is undeniable, and hawks sweep whole territories away on their flights of pillage, in pursuit of natural resources. Lies have been turned into an ideological discourse of a hegemonic nature, to build the rhetoric and “legal framework”, and erase any signs of singularity or dissent from our planet.

However, every power generates resistance, and the true possibility of building a different moral reality where cultures flow and come together in a logical atmosphere of respect and collaboration. The relationship between global and local – if it is not determined by the business interests of the strongest – can be harmonious and mutually beneficial. For this to be possible in today’s world, it is necessary to defend local cultures and strengthen people’s identity. A clear example is Old Havana’s Historical Core Restoration Program, which had Commander Fidel Castro’s support in the early 1990’s, because of the need to preserve national culture within the framework of the crisis following the collapse of the socialist camp. The entity responsible for this process is the Havana City Historian’s Office, led by Eusebio Leal Spengler, PhD (Historical Sciences), a Havana University Archeological Science expert, and a member of the Central Committee of the Cuban Communist Party.

The work carried out by Leal has attracted international recognition. In November 2007, he was presented with the Reina Sofía International Award in the category of Cultural Heritage Preservation and Restoration, for his important contribution to Old Havana’s restoration program, and its impact on the promotion of that historical core of the city. Mr. Leal was part of the Cuban mission that recently attended the 100th anniversary celebrations, on the occasion of the late former Chilean President Salvador Allende’s birthday, where he talked to Punto Final.

The Havana City Historian’s Office was created in 1937 by Emilio Roig de Leuchsenring – a historian, writer and journalist, with a profound knowledge of Cuban history. He also possessed a capability for advanced thinking, and took a strong anti-imperialist position. “He thought that creating a national awareness, and defending cultural values and the independence achieved by the Cuban people, were a key interpretation of our reality, thus allowing him to contravene official historiography,” Eusebio Leal said. In 1967, following his predecessor’s death, Leal took on responsibility for the restoration of the old government palace – the most important building in the historical center from a symbolic point of view. Restoration work spanned 11 years, and gained in prestige along the way. “If, due to circumstances, my predecessor could only develop basic academic work through which he opposed the outrages committed against historic buildings, it was so that a new historical period would give me the opportunity to carry out actual restoration work,” the Cuban executive maintained.

Protecting Culture

In 1994, in the middle of the crisis following the collapse of so-called real socialism, the Havana City Historian’s Office was granted financial autonomy under the State Council. How did you manage to successfully deal with the challenge of setting up an entity that was capable of undertaking a comprehensive city restoration process involving not only architectural, but also social, archeological and cultural issues, in such a difficult context?

“During that period, we had built up significant experience that led us to the conclusion that for a developing country, which was also faced with the crisis you mentioned; it was unviable to undertake a restoration project without regard to its social aspect. There were people living in our city, but above all we were fully involved in a social revolution from which we had been born. The situation worsened, and in 1993, Commander Fidel Castro told a number of intellectuals that it was necessary to save our nation’s culture. At that moment, there was public consensus that the City Historian’s Office was capable of leading that process. In October 1994, Fidel announced a decree-law, whereby our Office was granted an autonomous legal status with the right to own property and manage its own resources. Furthermore, he himself designed a mechanism so that we did not have to rely on hypothetical international cooperation that would almost certainly be symbolic. With it, he clearly expressed the State’s political will that Old Havana should be saved, but not sold out.”

The decision to preserve our cultural heritage the way you have done it, far from commercial criteria, involves an iron political will by the Revolution so that the values of socialism prevail. What has been the focus of your restoration process, and how does it differ from similar experiences in societies where private interests come before social interests?

“Any development project where culture is ignored generates nothing but decadence. The decree whereby our organization was incorporated, establishes that our entity may generate its own resources, provided that ethical, moral and spiritual values are placed above commercial interests. This takes on special significance in the context of tourism, where many people are not only interested in Cuba’s beaches and stereotyped image. They want to meet the people, learn about their resilience and culture – one of whose high points is the restoration work in Old Havana. There, tourists have the opportunity to become familiar with a project that is not only aimed at beautifying the city, but has also created jobs, trained young people in different construction-related trades, and both protected and promoted our cultural heritage.”

Irrespective of the mechanism that allows your Office to be self-financed, thus creating your own economic sector, have you established any kind of international cooperative relationship or agreement?

“In spite of the [US] blockade, we have secured international support from scientific organizations, universities and cooperation agencies, in such countries as Spain and Belgium. The Local Human Development Project (PDHL, Spanish initials) was created within the context of a UN initiative involving two key aspects in the restoration of a neighborhood where people actually live – monuments, and social and community aspects. This criterion has certainly been applied to Old Havana, which represents a small Sparta, striving for its fate – a true mirror of Cuba.”

Neither a Replica nor a Copy

You have described Havana as an eclectic city where different architectural styles merge, but at the same time, one with a very strong identity which demonstrates its Cubanness. Could you specify what those architectural styles are, and tell us how a city truthfully representing the local culture emerged from that amalgam of styles?

“The city marked a crossroads in the Americas when it was finally established in 1519. The island and the town are in the heart of the Mediterranean. That is why Cuba has always been described as an island from a geographic point of view, but not from a cultural standpoint, by the harbingers of our national thinking and identity. We have always looked to the continent we are a part of, but also to the world. That is how different [architectural] trends were introduced. First, ideas, then architecture and shape, together with contradictions and phenomena that were typical of a colonial society based on the exploitation of sugar, coffee, timber, and fleet trade – of which Havana was the central point. Therefore, it is not strange that architecture in Cuba’s historic cities, and particularly in Havana, is reflective of a world view – not a copy, but always an interpretation.”

An interpretation which is an amalgam of several cultures, where local identity prevails and is enriched.

“Nothing is as we are told, but as it is interpreted and then expressed in our geographical and climatological reality and, above all, in the essence of Cubanness. We are people of mixed blood and culture. Our origins reflect the Arab world through Spain, slaves from different parts of Africa, Judaism and Christianity, and indigenous footprints that were erased by the [Spanish] conquest. All of this gave rise to an identity of our own.”

It is an interesting reality showing that the global can harmonically come together with the local, and be mutually enriched. That is quite the opposite of what others seek to impose through neoliberal globalization – erasing local cultural identities to achieve absolute hegemony.

“The All and the We are nothing but a combination of individualities. In the revolution, the concept of people is a combination of individuals, and not their destruction. People’s full involvement, as well as their talent and creativity, are promoted. If this is analyzed on a worldwide scale, we note that it is important to accept that any modern age has necessarily been preceded by another; that we are experiencing a process that is more global than ever before in history, as a result of technological development and the media. Therefore, it is more important than ever to preserve the identity of each and every one of us. If, in this recognition process, we have struggled so much for unity, then we must also fight for singularity.”

One of the characteristics which is unique to the Cuban revolution, is that there is also a combination of the global and the local – from an ideological standpoint. Marx’s and Lenin’s contribution has been – and still is – of fundamental importance, and so have been the ideas and actions of José Martí, Félix Varela, José Antonio Saco, Fidel Castro and Che. What significance do you attach to this element, and what role has it played in the Revolution’s survival and scope?

“As Cuban avant-garde intellectuals became familiar with the most advanced thinking worldwide, they identified themselves with socialist ideals. However, there was a local precedent that was essential to us – José Martí. There are three basic sources in Fidel’s thinking – his Marxist and Christian training, and Martí’s ideas. Therefore, the discourse for Latin America had to be completely different. Che expressed that search for our own thinking and practice very well. The same way as Mariategui had previously stated the need for socialism not to be a copy, but a heroic creation. When we have been consistent with this, then we have approached the truth. Every time we have copied, we have been mistaken.”

In his book, Culture for Development, former Cuban Minister for Education and Culture, Armando Hart, wrote that the importance attached to education, culture and the promotion of ethical values has been central to the Revolution’s survival and strengthening. What is your view about it?

“According to the latest report by the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO), Cuba stands first in our continent in terms of education. That is, by the way, the result of tireless work by the revolution, which from its inception encouraged people’s education and culture. Constant promotion of values such as solidarity, generosity, willingness to collaborate with any other country around the world, and the Americanist vocation, have also been of fundamental importance. Our solidarity knows no bounds, and the sea, far from isolating us, has brought us closer. We share feelings that navigate easily thanks to our language, which has been our main strength, and has played a significant role in bringing us together. And for that, we should be thankful.”

How do you foresee the future of the Revolution? What challenges does it face?

“We celebrated ahead of time, the fall of the tenth US administration, whose aim was to destroy our process. We did it in the face of imperialism’s shame, in their eagerness to take control of Cuba; shame for their mendacious and criminal war in the Middle East, the disaster caused in the US economy, and the crisis it is dragging the world into. All of this reinforces our confidence in the reason that has motivated the Cuban people’s resilience as we approach the revolution’s 50th anniversary celebrations. We are without question facing new situations and challenges which require more daring interpretations of reality; we must reach out slowly, and with caution, to avoid the pitfalls of the complex world we live in. Our duty, however, is to consolidate the revolution’s social work, because we shall never give up our ideas, despite the fact that we have had our flesh shredded along the way to save it. We have been consistent, and believe that now – more than ever – solidarity, brotherhood and social justice are the only way.”

Compartir