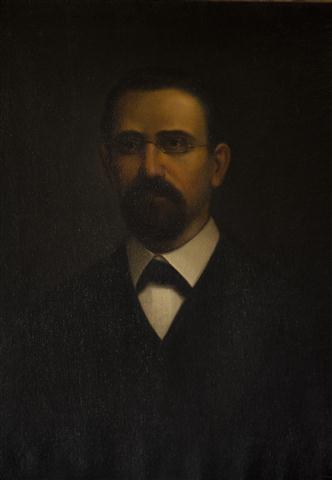

Eusebio Leal Spengler ~ Historiador de la Ciudad de La Habana ~

Let us Be Ready for Our Country’s New Destiny

(Stenographic Versions by the State Council)

Instead of continuing with the same thread that we have all heard, but rather that of our heart – the thread of reasons and motivations leading us to this Congress, I would like to remember, by evoking the start of this session, that unforgettable phrase the eminent French writer Marguerite Yourcenar – the author of Hadrian’s Memoirs – found in a letter by Flaubert: “Just when the gods had ceased to be, and the Christ had not yet come, there was a unique moment in history, between Cicero and Marcus Aurelius, when man stood alone.”

A meeting like this could not be held anywhere else in the world, because there is no such a place where intellectuals, writers and artists can meet and not just question, but also influence, and even determine with their ideas, the life of a whole State and nation. Such a privilege, which was given to us by time, is connected with how much we missed Fidel on the first day.

I would also like to say that when our General President was given such an ecstatic reception as once were Carlos Manuel de Céspedes, Salvador Cisneros Betancourt or Bartolomé Masó, I remembered the particular characteristics of our nation’s history.

I am a historian and, therefore, I have the habit of looking for explanations in that crystal ball. So, I reminisced about that episode of the 1868 Great War when a worthy man, who was incidentally misled, waylaid Antonio Maceo and pointed a revolver at his chest, disobeying Maceo’s orders. Maceo asked Limbano Sánchez – who later died heroically – to put down his gun and, when the latter obeyed, despite his bodyguard’s skeptical look, the Major General gave him a hug, and drew him toward the bosom of truth and reason.

The same thing happened during the struggle by the rebel forces in the Sierra [Maestra Mountains]. At the beginning, one of them was not happy with the way guns obtained in combat had been distributed, and tried to prove himself to the chief, saying that what was his would remain his. Then he gestured to wield his gun, but a man came and stood between the other two. That man is the General President who attended our Congress yesterday: I mean, Raúl. Had he not done so, perhaps we would not have a Revolution today.

We are not alone. Our nation is listening to what we are saying. Fidel is listening, and so was a deeply respectful Raúl yesterday.

In an overfamiliar manner, I once told the one I’m referring to: “You have forever condemned our nation to have a distinguished man as president.” And I was suffering for it. Today I think that distinguished Cubans – men and women – are here. You are a part – just a part – of them, because there are many others in the factories, at sea, in the armed forces, in sciences; but writers, pioneers, intellectuals – Cuba’s visible soul – are gathered here.

It will not be as in the Great War, when the cream of young intellectuals rode along with the President of the Republic in Arms –Bartolomé Masó – as part of his staff. When General Modesto Díaz – who did not understand much about art issues – saw them, he was so upset that he asked: “Mr. President, how come you surround yourself with these bandits?” The latter replied: “Why do you say such a thing about these young people?” And the former replied: “I do not know; I have been told that they are just poets.” Those poets were later immortalized by José Martí in his beautiful The War Poets, where he spoke of their originality. Nearly all of them signed their own written work with their blood.

I believe that Kcho – world-famous for his work; Desiderio Navarro – with his remarks; Frank Fernández with his, and each and every one of those who have spoken, have contributed to the essence of the problems under discussion.

We have arrived at this election in a democratic manner, and with no pressure. Otherwise, I would not dare speak at this venue. I do not want to be a quota Cuban; I just don’t. It would be offensive to be a quota Christian – and I am a Christian; or a quota mulatto – and I am a mulatto, by virtue of my blood and culture; or a quota black man, if I had a darker complexion. I want to be a part of this group, where no one has been chosen by anybody else’s finger. Cuba is like that, and if you try to change it by separating, dividing and turning it into a strange representation, then you would be missing José Martí’s legacy.

We have to assume that Juan Gualberto Gómez was José Martí’s most passionate and brilliant friend during the Teacher*’s last days of his life. We have to assume – as Dulce María Loynaz used to tell me – that as he loved Martí so much, he must have been devoted to Antonio Maceo – that other great man who is not very well known sometimes; an elegant, distinguished, refined and educated man by his own choice.

I believe that at UNEAC we should help to build today’s nation. We are all hopeful. Why? Because our country has really assumed that what was not convenient or prudent yesterday, is necessary today. Every day, the news we hear is more and more encouraging, and it is not a cosmetic issue – as our mortal enemies put it. Questions as deep as justice for farmers, who work the land, are being addressed; in 1959, and even before, that kind of justice was seen by my generation as the highest thing we could aspire to.

What we are supposed to do is fight, through our work, for all Cubans’ consciences to be cleansed and for the world to feel that those beautiful words by Martí are true: “What sweet mystery the word Cuban has!”

We feel such profound pride, as did Picasso when he welcomed a young Cuban man at a moment when it was something fabulous that a fellow countryman of ours became famous. Who was that young man? Wifredo Lam, who represented three sources of our blood – black, Chinese and Spanish. That is why he lived such a long life, as did José Luciano Franco, Regino Pedroso and Regino Botti, to mention but a few.

I feel, however, both happiness and sadness, in remembering Agustín Cárdenas’ tears when, beaten by disease, he was brought to Havana by Alejo Carpentier – his friend and admirer. When he was awarded the Legion of Honor – the supreme order awarded by France, which Claudio José Domingo Brindis de Salas had also been presented with – Cárdenas was unable to speak because he was already fatally ill. But, perhaps the most serious disease was the fact that he was not known by Cubans. He was recognized by France, by Alejo, and by Picasso, but the great sculptor was barely known in his homeland.

Cuba needs to think that, at this moment, and along the path we have chosen, we could have an illustrious group of outstanding and great persons – if we do not consider age as an inconvenience, lest we are also accused of planning to proclaim an intellectual gerontocracy. Young people should not forget, however, that youth is the only disease that is cured over time. Please, do not forget that! You could especially think that we could be honored by the venerable Cintio Vitier – a notable philosopher’s son, a rebel general’s grandson, a father of musicians and a writer’s grandfather. Silvio [Rodríguez] or Pablo [Milanés], who have made Cuban songs world famous, could be here as well. And they are here within us. And, like Don Quixote, they will stand out anywhere they go because of their commendable work. Their talent has elevated them as artists, winning great glory at every public space, when Cuba was a cursed name.

I am not ashamed of what we are doing; on the contrary, I think that we are doing the right thing, and that you are right, Kcho – you are right, because when you painted your ships, and put up your installations, many people said: “This guy is celebrating rafting.” No, no. You are – as I once told you – the son of Yemayá Olokun, of Havana port, of the blue ocean, and your ships are placed at the entrance. But they are not departing, they are returning.

I am not ashamed of those who are abroad, because my children are abroad, and I will never be ashamed of my fatherhood, nor will I ever deprive them of their Cuban condition. They decided which way they wanted to go. As long as they do not take up arms against their homeland, or raise their hand against he who gave them their name – as long as they do not do that, they will continue to be my children. Otherwise, I would have to say that all of those fighting for Cuba’s independence are also my children – as our Founding Father once said.

Right now, and from my heart, I would like to send a message of gratitude to him [Fidel] as he recovers from his illness; he is not here because he can’t be, not because he does not want to be. I wish I could be a walking stick, like that of Aeneas, to hold him – he whose work cleared the way for us to do ours. That is what I believe now.

Let us be prepared for our country’s new destiny. Let us think that these honorable comrades from the scrutiny commission have done the right thing. In my view, no one should be left out. There is no omission, because I admire poetry by Reina María Rodríguez, as much as that by Avellaneda, who was under discussion, because she had lived outside of Cuba and wrote that passionate and harsh poem titled In departing.

A few days ago, I looked for her tomb at Seville cemetery, and the tombstone read: “To the honorable Mrs. Gertrudis Gómez de Avellaneda.” That is how I love any other woman, or any other Cuban who has truly contributed to our country, without ever deviating – and please hear me well – from the defence of our long-besieged land.

It is a miracle that we are able to meet now. Some day, the history of what these ten years have been like will be written. It’s a good thing that now it is legal to have a cell phone! There was a moment when we could not even communicate. It is a good thing that the founding communists’ song – you own the land that you work on, as you own your bitter sweat – has been fulfilled, so that we can have in Cuba, everything we need; then, the speculators, the weasels, bleeding us dry, will fall apart.

[It will be a good thing] when working farmers are respected, and no one walking past their rural houses will ever say: “That bastard got himself a car,” at the sight of an old, but painted, car at the entrance; even though they do not know how hard it’s owner had to work on the land to obtain the fruit of his labors.

It is necessary, when they see any one of us walking by, no matter how peculiar we may be, that we are shown respect and esteem. People should never say – as we did at the beginning of the Revolution – “There goes a little black man” or “There goes a homosexual” or – as we live in a literary Republic and it’s a very Spanish-like expression “There goes a fag.” No! No! If we have struggled so hard for our freedom, may our peculiarity be respected as well! That is what we have achieved at this meeting and that is why we have come this far.

We have overcome, because we have survived. When everything is over, perhaps, dear Fidel and dear friends, I will be able to say, as Abbot Sieyés said when someone asked: “What did you do?” during those terrible days of the French Revolution, – which were not ours.

He answered in a cry of honesty: “Me, I survived it.”

Thank you very much.

*Translator’s Notes: – UNEAC means National Union of Cuban Writers and Artists, Spanish initials.

– The Teacher (El Maestro) is one way our National Hero José Martí is usually referred to.

Compartir